Starter Kit: “Hacking Virtual Worlds: Video Games and Critical Infrastructure Studies”

![]()

Description

How might we re-think game studies in relation to the emergent field of critical infrastructure studies, and vice versa? Further, how might games themselves teach us new ways of understanding, developing, reconfiguring, and even “hacking” infrastructure? If we understand infrastructure as a convergence and entanglement of Marx’s base and superstructure—a point at which culture and material technology intertwine—do we find a way out of the relentless emphasis on harder and harder materialities, of the ongoing persistence to go deeper (e.g. from screen essentialism to software to hardware to geological minerals (as in Parikka’s A Geology of Media))? In certain games, might we find infrastructures, and not merely “representations” of infrastructure, on our screens? In addition to putting CIS in conversation with game studies, this starter kit assembles what we might loosely categorize as a “critical hacking” genre, in which the user interacts with computational infrastructures that blur the divisions between content and medium, representation and real.

![]()

Readings

Framing

- Alan Liu. “Toward Critical infrastructure Studies.” Adapted version of paper last presented in full at University of Connecticut, Storrs, February 23, 2017. http://cistudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Toward-Critical-Infrastructure-Studies.pdf

- Walt Scacchi. “Computer Game Mods, Modders, Modding, and the Mod Scene.” First Monday, vol. 15, no. 5, 2010. https://firstmonday.org/article/view/2965/2526

- ______. “Modding as an Open Source Approach to Extending Computer Game Systems.” Open Source Systems: Grounding Research, Proc. 7th IFIP Intern Conf. Open Source Systems. eds. S. Hissam, B. Russo, M.G. de Mendonca Neto, and F. Kan. IFIP ACIT 365, (Best Paper award), Salvador, Brazil, October 2011, 62-74. https://www.ics.uci.edu/~wscacchi/Papers/New/Scacchi-OSS2011.pdf

![]()

Foundations

A Brief Bibliography of Game Studies and Media Theoretical Approaches. While none of these take an explicitly infrastructural approach, in combination (or perhaps, ‘conversation’), they form the foundation for an infrastructural approach to game studies.

Platform Studies

- Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost. Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. 2nd edition, The MIT Press, 2009. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/racing-beam

Software or Algorithmic Studies

- Alexander Galloway. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. First edition, University Of Minnesota Press, 2006. http://art.yale.edu/file_columns/0000/1536/galloway_ar_-_gaming_-_essays_on_algorithmic_culture.pdf

- Noah Wardrip-Fruin. Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies. The MIT Press, 2012.https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/expressive-processing

- Lev Manovich. The Language of New Media. The MIT Press, 2002.https://dss-edit.com/plu/Manovich-Lev_The_Language_of_the_New_Media.pdf

- ______. Software Takes Command. 1st Edition, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.http://softwarestudies.com/softbook/manovich_softbook_11_20_2008.pdf

Narratology

- Espen Aarseth. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. UK edition, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. https://monoskop.org/images/e/e0/Aarseth_Espen_J_Cybertext_Perspectives_on_Ergodic_Literature.pdf

Media Archaeology/Hardware Studies

- Friedrich Kittler. Literature, Media, Information Systems. Edited by John Johnston, 1st edition, Routledge, 1997. https://monoskop.org/log/?p=9991

- Jussi Parikka. A Geology of Media. University Of Minnesota Press, 2015. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/a-geology-of-media

Tactical Media

- Rita Raley. Tactical Media. Minnesota Press, 2009. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/tactical-media

- Geert Lovink. Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture. The MIT Press, 2002. https://monoskop.org/images/3/32/Lovink_Geert_Dark_Fiber_Tracking_Critical_Internet_Culture_2002.pdf

- Michel de Certeau. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 1984. https://monoskop.org/images/2/2a/De_Certeau_Michel_The_Practice_of_Everyday_Life.pdf

Cultural Studies

- Mia Consalvo. Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. The MIT Press, 2009. https://is.muni.cz/el/1421/podzim2013/IM082/um/Consalvo__Cheating__Gaining_Advantage_in_Videogames.pdf

![]()

Gallery of Games

While most of game studies points to the universal—e.g. developing theories that apply to all video games—this starter kit assembles a selection of infrastructural games in order to further demonstrate the relevance of critical infrastructure studies within this field. There’s an obvious shortcoming here: the theory developed out of analyzing these games will not necessarily (or likely) apply to all games; it is an admittedly limited theoretical approach. But the universalizing tendency renders the specifics of the games mute–under-appreciating how games themselves play a role in developing the theory. Rather than applying an already developed theoretical approach to games, this starter kit thinks with a specific set of games in order to develop a broader intervention into infrastructural theory. Or, in other words, the games are just as much participants as the players.

Origins

Hacking games emerged during the mid-1980’s on platforms such as Commodore 64, Apple II, and MS-DOS. Arguably, these games set the stage for the design of the hacking genre, from System 15000 and Hacker’s early desktop or command center interface to the more adventure game interface of Neuromancer, combining both navigable space in the character’s world, as well as within a computational network.

System 15000 (1984)

First Hacking Simulation

Hacker series

Neuromancer (1988)

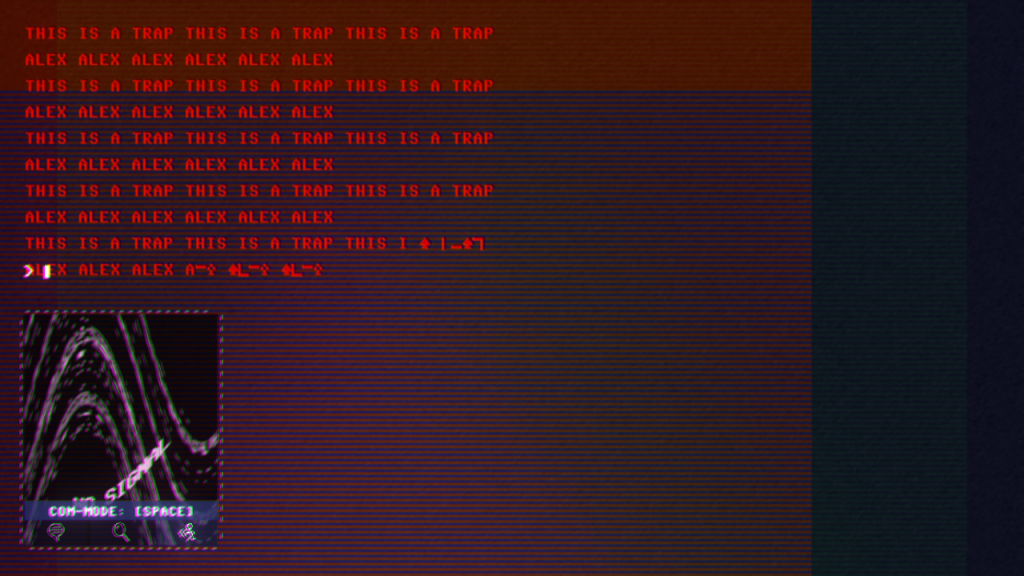

Desktop Simulations

These games simulate the contemporary computer desktop to varying degrees of accuracy. Some, such as Hacknet, even simulate the Linux command line, requiring the player to learn actual Linux commands in order to progress through the game. Lacking the adventure world environment, these games promote an immersive experience (similar to Bolter and Grusin’s notion of “immediacy”) in which the player can perceive the simulated desktop as their own (with the aid of some suspension of disbelief).

|

|

|

| Hacknet (2015) | ||

|

|

Uplink (2001)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Code 7 (2017) | ||

Hardware and Engineering

Largely dominated by Zachronics Industries, this sub-genre places the player in the role of the computer engineer, requiring them to build and configure the hardware components of the computer.

|

|

|

|

TIS-100 (2015)

|

|

Shenzhen I/O (2016)

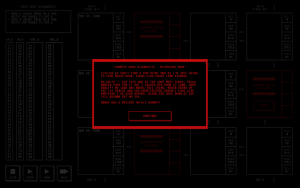

Meta-Infrastructural

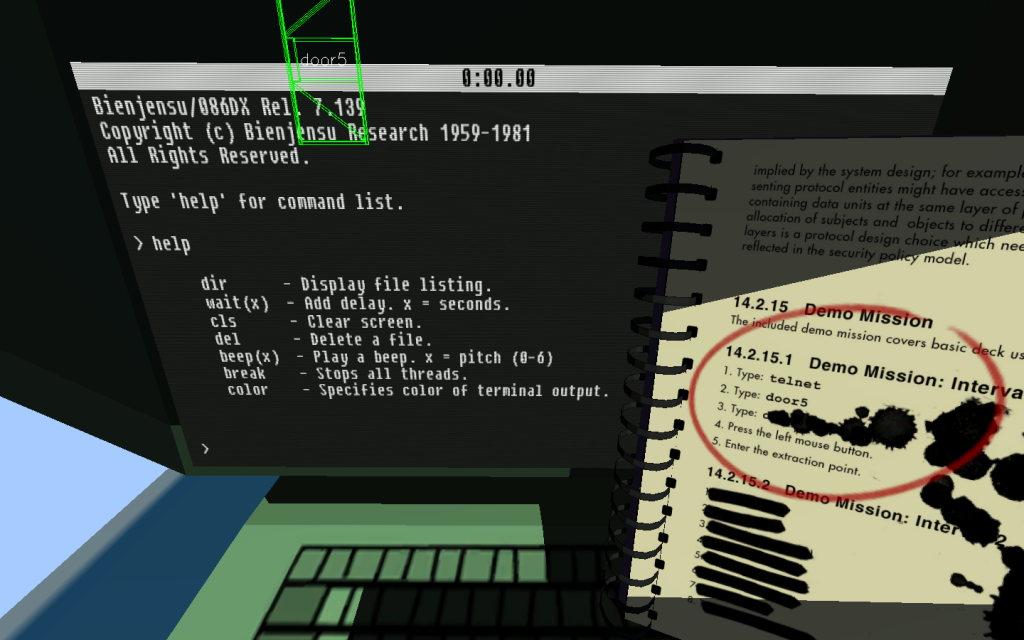

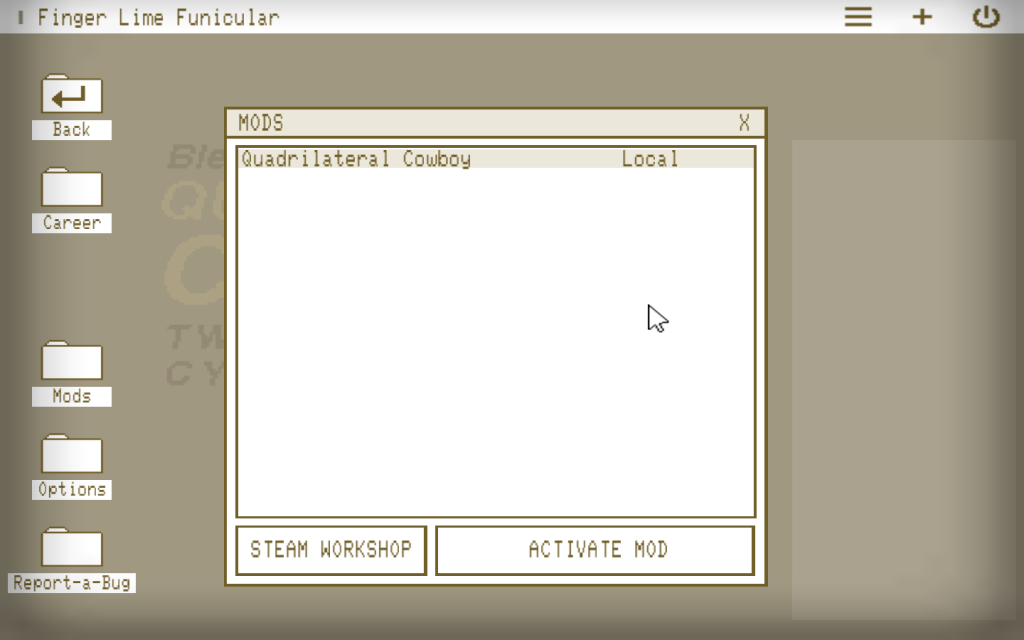

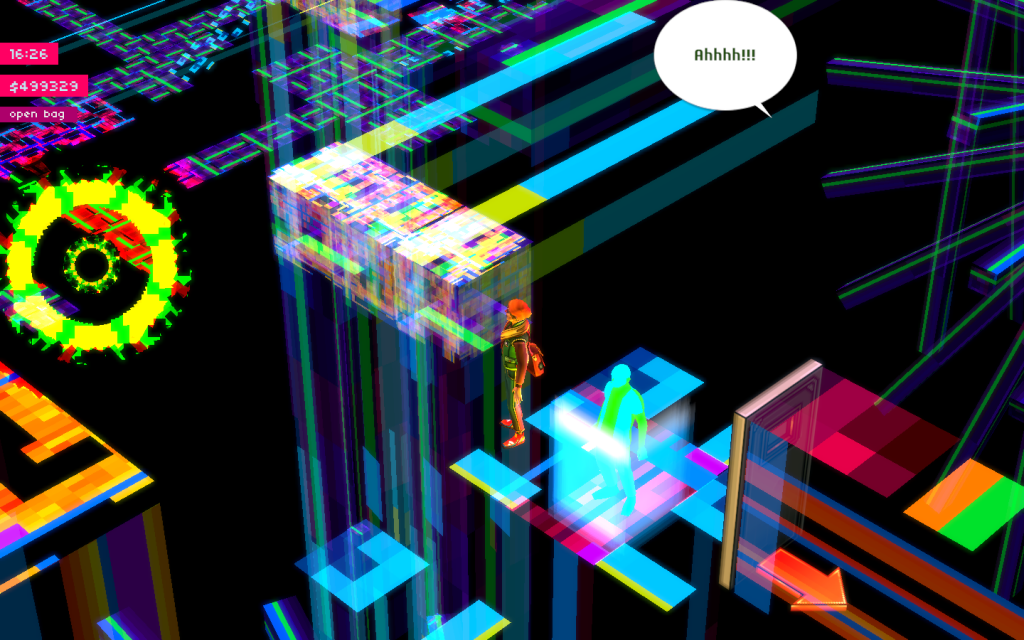

Here, the genre appears to reach a kind of apotheosis, in which game designers realize the potential for games to not only simulate (or represent) hacking, but actually encourage (even require) players to hack the game itself, through reprogramming the game world within the game and/or through modding the game’s system files. For a more detailed account of this genre, please see my case study of else Heart.Break().

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quadrilateral Cowboy (2016) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pony Island (2016) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| else Heart.Break() (2015) | ||

![]()

Additional Materials

An assortment of other materials for those interested in pursuing the focus of this starter kit further.

- Ryan Leach. “Back to the Screen?: Video Games and Critical Infrastructure Studies.” Web Blog. Frettings on the Blank. 9 Dec. 2018. https://ryankleach.github.io/frettingsontheblank/back-to-the-screen/

- —. “Hacking Games: else Heart.Break().” Web Blog. Frettings on the Blank. 10 Dec. 2018. https://ryankleach.github.io/frettingsontheblank/hacking-games-else-heartbreak/